The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story of Hiawatha, by

Winston Stokes and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Story of Hiawatha

Adapted from Longfellow

Author: Winston Stokes

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Illustrator: M. L. Kirk

Release Date: April 9, 2010 [EBook #31926]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF HIAWATHA ***

Produced by Emmy, Tor Martin Kristiansen and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

[i]

THE STORY OF HIAWATHA

[iv]

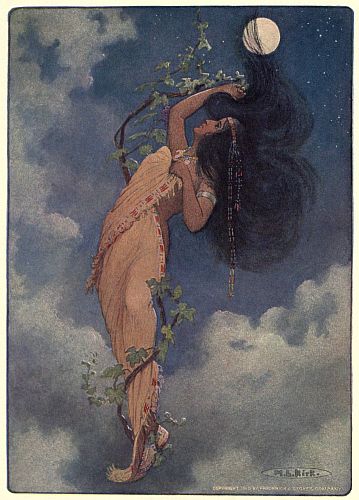

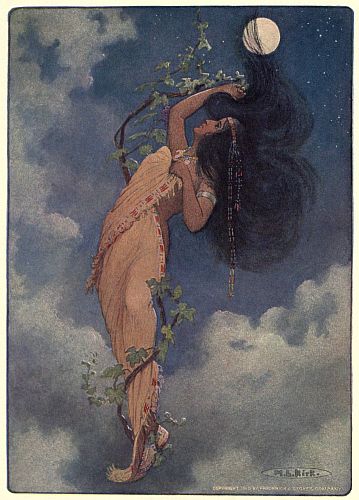

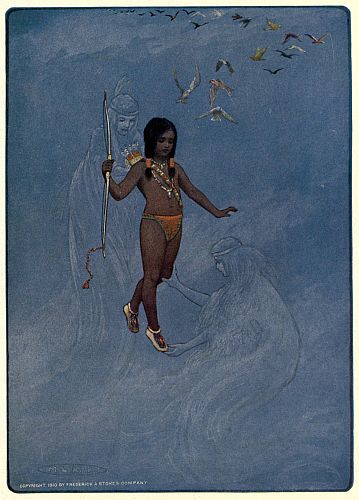

"FROM THE FULL MOON FELL NOKOMIS"—Page 123

"FROM THE FULL MOON FELL NOKOMIS"—Page 123

[v]

THE STORY OF HIAWATHA

ADAPTED FROM

:LONGFELLOW:

BY

WINSTON STOKES

WITH THE ORIGINAL POEM

Illustrated by

M · L · KIRK

NEW YORK

FREDERICK · A · STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

[vi]

Copyright, 1910, By

Frederick A. Stokes Company

All rights reserved

September, 1910

[vii]

PREFACE

In this land of change it is important that we may

learn a little of the childlike people who preceded us; who

hunted, fished and worshipped long ago where we now

make our homes and lead our lives. No other legends have

so strange a charm, or such appealing local interest, as legends

of the wildwood, and nowhere are these so well expressed

as in Longfellow's poem of Hiawatha.

To furnish a simple medium through which both younger

and older people of today may be brought closer, by Longfellow,

to the mystery of the forest, this prose rendering of

"Hiawatha" has been written. It follows closely the narrative

of the poem, and in many places Longfellow's own

words have been introduced into its pages, for the purpose

of this volume is to awaken interest and pleasure in the

poem itself.

[ix]

CONTENTS

THE STORY OF HIAWATHA

| | PAGE |

| Preface | vii |

| CHAPTER |

| I. | The Peace-Pipe | 1 |

| II. | The Four Winds | 3 |

| III. | Hiawatha's Childhood | 11 |

| IV. | Hiawatha and Mudjekeewis | 15 |

| V. | Hiawatha's Fasting | 19 |

| VI. | Hiawatha's Friends | 23 |

| VII. | Hiawatha's Sailing | 27 |

| VIII. | Hiawatha's Fishing | 30 |

| IX. | Hiawatha and the Pearl-Feather | 34 |

| X. | Hiawatha's Wooing | 38 |

| XI. | Hiawatha's Wedding Feast | 43 |

| XII. | The Son of the Evening Star | 47 |

| XIII. | Blessing the Cornfields | 53 |

| XIV. | Picture Writing | 57 |

| XV. | Hiawatha's Lamentation | 60 |

| XVI. | Pau-Puk-Keewis | 65 |

| XVII. | The Hunting of Pau-Puk-Keewis | 70 |

| XVIII. | The Death of Kwasind | 76 |

| XIX. | The Ghosts | 80 |

| XX. | The Famine | 84 |

| XXI. | The White Man's Foot | 88 |

| XXII. | Hiawatha's Departure | 92 |

[x]

CONTENTS

THE SONG OF HIAWATHA

| | PAGE |

| Introduction | 99 |

| CANTO |

| I. | The Peace-Pipe | 105 |

| II. | The Four Winds | 111 |

| III. | Hiawatha's Childhood | 123 |

| IV. | Hiawatha and Mudjekeewis | 133 |

| V. | Hiawatha's Fasting | 144 |

| VI. | Hiawatha's Friends | 156 |

| VII. | Hiawatha's Sailing | 163 |

| VIII. | Hiawatha's Fishing | 168 |

| IX. | Hiawatha and the Pearl-Feather | 178 |

| X. | Hiawatha's Wooing | 189 |

| XI. | Hiawatha's Wedding Feast | 200 |

| XII. | The Son of the Evening Star | 210 |

| XIII. | Blessing the Cornfields | 225 |

| XIV. | Picture Writing | 234 |

| XV. | Hiawatha's Lamentation | 241 |

| XVI. | Pau-Puk-Keewis | 250 |

| XVII. | The Hunting of Pau-Puk-Keewis | 260 |

| XVIII. | The Death of Kwasind | 274 |

| XIX. | The Ghosts | 279 |

| XX. | The Famine | 288 |

| XXI. | The White Man's Foot | 295 |

| XXII. | Hiawatha's Departure | 304 |

[xi]

ILLUSTRATIONS

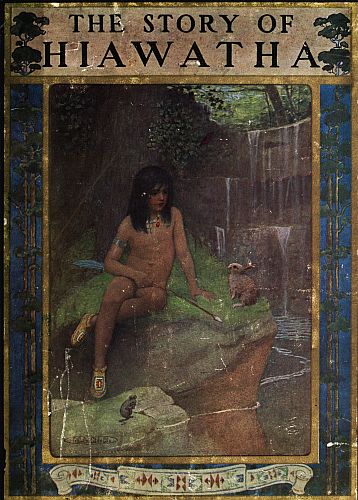

| "Of All Beasts He Learned the Language" | Cover |

| "From the Full Moon Fell Nokomis" | Frontispiece |

| | FACING PAGE |

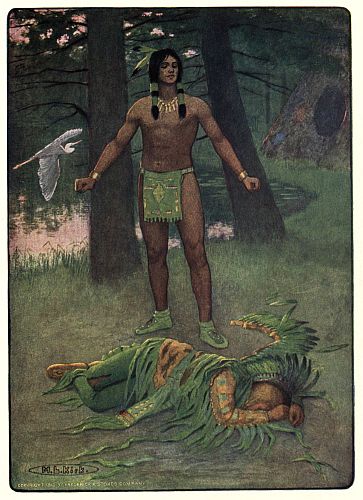

| "Dead He Lay There In the Sunset" | 22 |

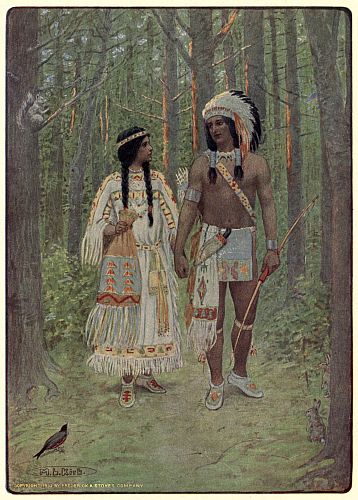

| "Pleasant Was the Journey Homeward" | 42 |

| "Seven Long Days and Nights He Sat There" | 86 |

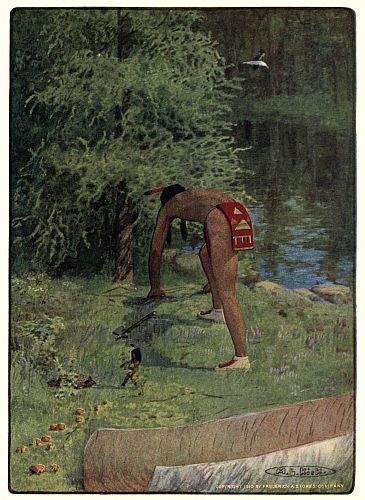

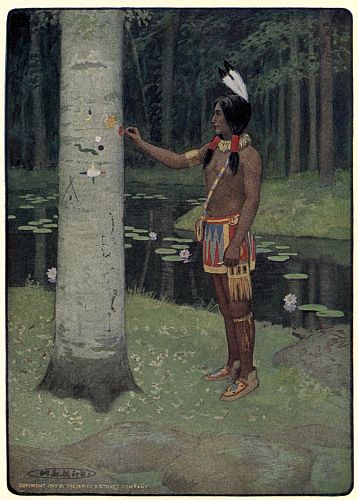

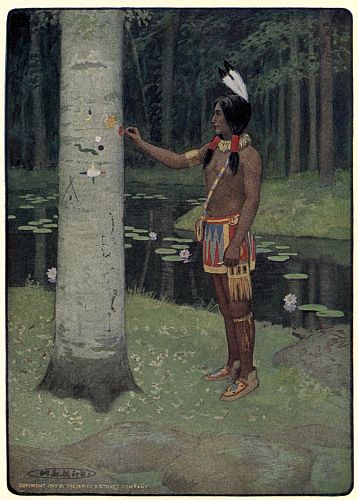

| "Give Me Of Your Roots, O Tamarack" | 164 |

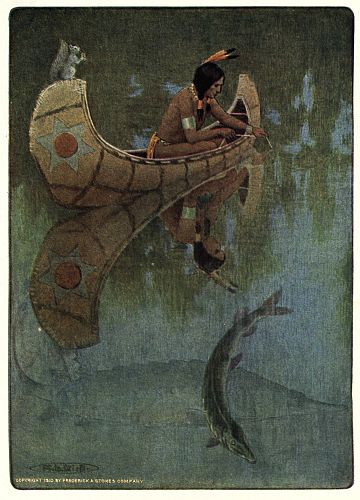

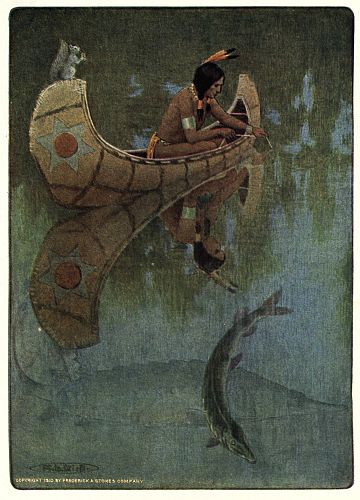

| "Take My Bait, O King of Fishes" | 170 |

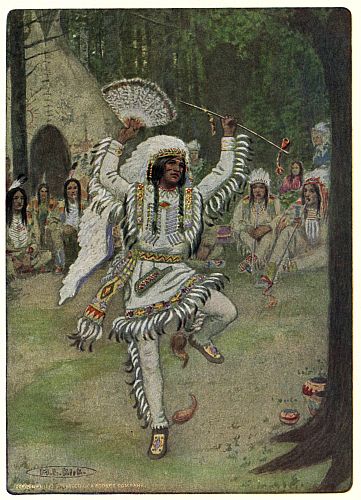

| He Began His Mystic Dances | 204 |

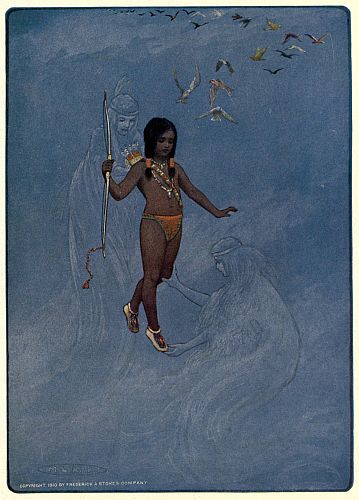

| "Held By Unseen Hands But Sinking" | 222 |

| "And Each Figure Had a Meaning" | 236 |

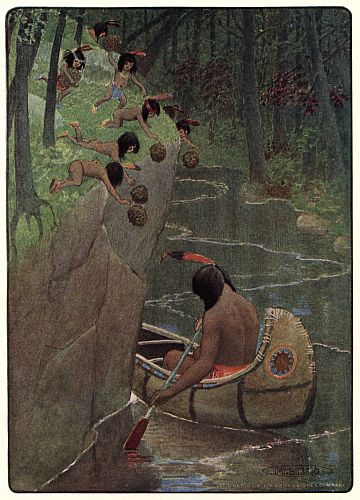

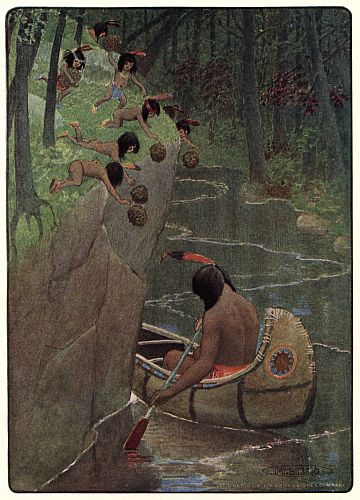

| "Hurled the Pine Cones Down Upon Him" | 278 |

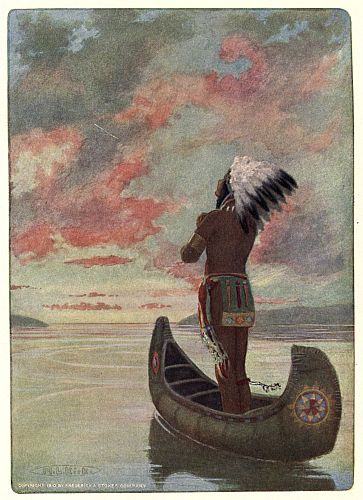

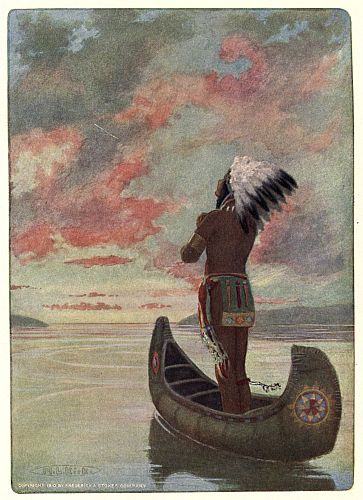

| "Westward, Westward Hiawatha Sailed Into the Fiery Sunset" | 310 |

[1]

THE STORY OF HIAWATHA

I

THE PEACE-PIPE

LONG ago, when our cities were pleasant woodlands

and the white man was far beyond the seas, the

great Manito, God of all the Indians, descended to the

earth. From the red crags of the Great Red Pipestone

Quarry he gazed upon the country that he ruled, and a silver

river gushed from his footprints and turned to gold

as it met the morning sun. The Great Manito stooped to

gather some of the red stone of the quarry, and molded it

with giant fingers into a mighty pipe-bowl; he plucked a

reed from the river bank for a pipe-stem, filled the pipe

with the bark of the willow, breathed upon the forest until

the great boughs chafed together into flame, and there

alone upon the mountains he smoked the pipe of peace.

The smoke rose high and slowly in the air. Far above the

tops of the tallest pine-trees it rose in a thin blue line, so

that all the nations might see and hasten at the summons of

the Great Manito; and the smoke as it rose grew thicker and

purer and whiter, rolling and unfolding in the air until it

[2]

glistened like a great white fleecy cloud that touched the

top of heaven. The Indians saw it from the Valley of

Wyoming, and from Tuscaloosa and the far-off Rocky

Mountains, and their prophets said: "Come and obey the

summons of the Great Manito, who calls the tribes of men

to council!"

Over the prairies, down the rivers, through the forests,

from north and south and east and west, the red men hastened

to approach the smoke-cloud. There were Delawares

and Dacotahs and Choctaws and Comanches and

Pawnees and Blackfeet and Shoshonies,—all the tribes of

Indians in the world, and one and all they gathered at

the Pipestone Quarry, where the Great Manito stood and

waited for them. And the Great Manito saw that they

glared at one another angrily, and he stretched his right

hand over them and said:

"My children, I have given you a happy land, where you

may fish and hunt. I have filled the rivers with the trout

and sturgeon. There are wild fowl in the lakes and

marshes; there are bears in the forest and bison on the

prairie. Now listen to my warning, for I am weary of

your endless quarrels: I will send a Prophet to you,

who shall guide you and teach you and share your sufferings.

Obey him, and all will be well with you. Disobey

him, and you shall be scattered like the autumn

leaves. Wash the war-paint and the bloodstains from[3]

your bodies; mould the red stone of the quarry into peace-pipes,

and smoke with me the pipe of peace and brotherhood

that shall last forever."

The tones of his deep voice died away, and the Indians

broke their weapons and bathed in the sparkling river.

They took the red stone of the quarry and made peace-pipes

and gathered in a circle; and while they smoked the

Great Manito grew taller and mightier and lighter until

he drifted on the smoke high above the clouds into the

heavens.

II

THE FOUR WINDS

IN the far-off kingdom of Wabasso, the country of the

North-wind, where the fierce blasts howl among the

gorges and the mountains are like flint the year round,

Mishe Mokwa, the huge bear, had his cave. Years

had passed since the great Manito had spoken to the

tribes of men, and his words of warning were forgotten

by the Indians; the smoke of his peace-pipe had been blown

away by the four winds, and the red men smeared their

bodies with new war-paint, as they had done in days of old.

But, brave as they were, none of them dared to hunt the

monster bear, who was the terror of the nations of the

earth. He would rise from his winter sleep and bring the

[4]

fear of death into the villages, and he would come like a

great shadow in the night to kill and to destroy. Year

by year the great bear became bolder, and year by year

the number of his victims had increased until the mighty

Mudjekeewis, bravest of all the early Indians, grew into

manhood.

Although Mudjekeewis was so strong that all his enemies

were afraid of him, he did not love the war-path, for

he alone remembered the warning of the great Manito;

and as he wished to be a hero, and yet to do no harm to his

fellow men, he decided to hunt and kill the great bear of

the mountains, and to take the magic belt of shining shells

called wampum that the great bear wore about his neck.

Mudjekeewis told this to the Indians, and one and all they

shouted: "Honor be to Mudjekeewis!"

For a weapon he took a huge war-club, made of rock and

the trunk of a tough young pine, and all alone he went

into the Northland to the home of Mishe Mokwa. Many

days he hunted, for the great bear knew of his coming,

and the monster's savage heart felt fear for the first time;

but at last, after a long search, Mudjekeewis heard a sound

like far-off thunder, that rose and fell and rose again

until the echoes all around were rumbling, and he knew

the sound to be the heavy breathing of the giant bear, who

slept. Softly Mudjekeewis stole upon him.

The great bear was sprawled upon the mountain, so[5]

huge that his fore-quarters rose above the tallest boulders,

and on his rough and wrinkled hide the belt of wampum

shone like a string of jewels. Still he slept; and Mudjekeewis,

almost frightened by the long red talons and the

mighty arms and fore-paws of the monster, drew the shining

wampum softly over the closed eyes and over the grim

muzzle of the bear, whose heavy breathing was hot upon

his hands.

Then Mudjekeewis gripped his club and swung it high

above his head, shouting his war-cry in a terrible voice,

and he struck the great bear on the forehead a blow that

would have split the rocks on which the monster slept.

The great bear rose and staggered forward, but his senses

reeled and his legs trembled beneath him. Stunned, he

sat upon his haunches, and from his mighty chest and

throat came a little whimpering cry like the crying of a

woman. Mudjekeewis laughed at the great bear, and

raising his war-club once again, he broke the great bear's

skull as ice is broken in winter. He put on the belt of

wampum and returned to his own people, who were proud

of him and cried out with one voice that the West-wind

should be given him to rule. Thenceforth he was known

as Kabeyun, father of the winds and ruler of the air.

Kabeyun had three sons, to whom he gave the three

remaining winds of heaven. To Wabun he gave the

steady East-wind, fresh and damp with the air of the[6]

ocean; to the lazy Shawondasee he gave the scented breezes

of the south, and to the cruel Kabibonokka he gave the icy

gusts and storm-blasts of the Northland.

Wabun, the young and beautiful, ruled the morning,

and would fly from hill to hill and plain to plain awakening

the world. When he came with the dew of early dawn

upon his shoulders the wild fowl would splash amid the

marshes and the lakes and rivers wrinkle into life. The

squirrels would begin to chatter in the tree-tops, the moose

would crash through the thicket, and the smoke would rise

from a thousand wigwams.

And yet, although the birds never sang so gayly as when

Wabun was in the air, and the flowers never smelled so

sweet as when Wabun blew upon their petals, he was not

happy, for he lived alone in heaven. But one morning,

when he sprang from the cloud bank where he had lain

through the night, and when he was passing over a yet

unawakened village, Wabun saw a maiden picking rushes

from the brink of a river, and as he passed above her she

looked up with eyes as blue as two blue lakes. Every

morning she waited for him by the river bank, and Wabun

loved the beautiful maiden. So he came down to earth

and he wooed her, wrapped her in his robe of crimson till

he changed her to a star and he bore her high into the

heavens. There they may be seen always together, Wabun

and the pure, bright star he loves—the Star of Morning.[7]

But his brother, the fierce and cruel Kabibonokka, lived

among the eternal ice caves and the snowdrifts of the

north. He would whisk away the leaves in autumn and

send the sleet through the naked forest; he would drive the

wild fowl swiftly to the south and rush through the

woods after them, roaring and rattling the branches.

He would bind the lakes and rivers in the keenest, hardest

ice, and make them hum and sing beneath him as he whirled

along beneath the stars, and he would cause great floes and

icebergs to creak and groan and grind together in agony of

cold.

Once Kabibonokka was rushing southward after the departing

wild fowl, when he saw a figure on the frozen moorland.

It was Shingebis, the diver, who had stayed in the

country of the North-wind long after his tribe had gone

away, and Shingebis was making ready to pass the winter

there in spite of Kabibonokka and his gusty anger. He

was dragging strings of fish to his winter lodge—enough

to last him until spring should set the rivers free and fill

the air once more with wild fowl and the waters with returning

salmon.

What did Shingebis care for the anger of Kabibonokka?

He had four great logs to burn as firewood (one for each

moon of the winter), and he stretched himself before the

blazing fire and ate and laughed and sang as merrily as if

the sun were warm and bright without his cheery wigwam.[8]

"Ho," cried Kabibonokka, "I will rush upon him! I will

shake his lodge to pieces! I will scatter his bright fire and

drive him far to the south!" And in the night Kabibonokka

piled the snowdrifts high about the lodge of Shingebis, and

shook the lodge-pole and wailed around the smoke-flue

until the flames flared and the ashes were scattered on the

floor. But Shingebis cared not at all. He merely turned

the log until it burned more brightly, and laughed and sang

as he had done before, only a little louder: "O Kabibonokka,

you are but my fellow-mortal!"

"I will freeze him with my bitter breath!" roared Kabibonokka;

"I will turn him to a block of ice," and he burst

into the lodge of Shingebis. But although Shingebis knew

by the sudden coldness on his back that Kabibonokka stood

beside him, he did not even turn his head, but blew upon

the embers, struck the coals and made the sparks flicker up

the smoke-flue, while he laughed and sang over and over

again: "O Kabibonokka, you are but my fellow-mortal!"

Drops of sweat trickled down Kabibonokka's forehead,

and his limbs grew hot and moist and commenced to melt

away. From his snow-sprinkled locks the water dripped

as from the melting icicles in spring, and the steam rose

from his shoulders. He rushed from the lodge and howled

upon the moorland; for he could not bear the heat and the

merry laughter and the singing of Shingebis, the diver.

"Come out and wrestle with me!" cried Kabibonokka.[9]

"Come and meet me face to face upon the moorland!" And

he stamped upon the ice and made it thicker; breathed upon

the snow and made it harder; raged upon the frozen marshes

against Shingebis, and the warm, merry fire that had driven

him away.

Then Shingebis, the diver, left his lodge and all the

warmth and light that was in it, and he wrestled all night

long on the marshes with Kabibonokka, until the North-wind's

frozen grasp became more feeble and his strength

was gone. And Kabibonokka rose from the fight and fled

from Shingebis far away into the very heart of his frozen

kingdom in the north.

Shawondasee, the lazy one, ruler of the South-wind,

had his kingdom in the land of warmth and pleasure of the

sunlit tropics. The smoke of his pipe would fill the air

with a dreamy haze that caused the grapes and melons to

swell into delicious ripeness. He breathed upon the fields

until they yielded rich tobacco; he dropped soft and starry

blossoms on the meadows and filled the shaded woods with

the singing of a hundred different birds.

How the wild rose and the shy arbutus and the lily, sweet

and languid, loved the idle Shawondasee! How the frost-weary

and withered earth would melt and mellow at his

sunny touch! Happy Shawondasee! In all his life he

had a single sorrow—just one sleepy little sting of pain.

He had seen a maiden clad in purest green, with hair as[10]

yellow as the bright breast of the oriole, and she stood and

nodded at him from the prairie toward the north. But

Shawondasee, although he loved the bright-haired maiden

and longed for her until he filled the air with sighs of

tenderness, was so lazy and listless that he never sought

to win her love. Never did he rouse himself and tell her

of his passion, but he stayed far to the southward, and

murmured half asleep among the palm-trees as he dreamed

of the bright maiden.

One morning, when he awoke and gazed as usual toward

the north, he saw that the beautiful golden hair of the

maiden had become as white as snow, and Shawondasee

cried out in his sorrow: "Ah, my brother of the North-wind,

you have robbed me of my treasure! You have

stolen the bright-haired maiden, and have wooed her with

your stories of the Northland!" and Shawondasee wandered

through the air, sighing with passion until, lo and

behold! the maiden disappeared.

Foolish Shawondasee! It was no maiden that you

longed for. It was the prairie dandelion, and you puffed

her away forever with your useless sighing.

[11]

III

HIAWATHA'S CHILDHOOD

NO doubt you will wonder what the stories of the

Four Winds have to do with Hiawatha, and why

he has not been spoken of before; but soon you will see

that if you had not read these stories, you could not

understand how the life of Hiawatha was different from

that of any other Indian. And Hiawatha had been chosen

by the great Manito to be the leader of the red men, to

share their troubles and to teach them; so of course there

were a great many things that took place before he was

born that have to be remembered when we think of him.

In the full moon, long ago, the beautiful Nokomis was

swinging in a swing of grape-vines and playing with her

women, when one of them, who had always wished to do

her harm, cut the swing and let Nokomis fall to earth. As

she fell, she was so fair and bright that she seemed to be a

star flashing downward through the air, and the Indians

all cried out: "See, a star is dropping to the meadow!"

There on the meadow, among the blossoms and the

grasses, a daughter was born to Nokomis, and she called

her daughter Wenonah. And her daughter, who was born

beneath the clear moon and the bright stars of heaven, grew

into a maiden sweeter than the lilies of the prairie, lovelier[12]

than the moonlight and purer than the light of any star.

Wenonah was so beautiful that the West-wind, the

mighty West-wind, Mudjekeewis, came and whispered

tenderly into her ear until she loved him. But the West-wind

did not love Wenonah long. He went away to his

kingdom on the mountains, and after he had gone Wenonah

had a son whom she named Hiawatha, the child of the

West-wind. But Wenonah was so sad because the West-wind

had deserted her that she died soon after Hiawatha

was born, and the infant Hiawatha, without father or

mother, was taken to Nokomis' wigwam, which stood

beside a broad and shining lake called "The Big-Sea-Water."

There he lived and was nursed by his grandmother,

Nokomis, who sang to him and rocked him in his cradle.

When he cried Nokomis would say to him: "Hush, or the

naked bear will get thee," and when he awoke in the night

she taught him all about the stars, and showed him the

spirits that we call the northern lights dance the Death-dance

far in the north.

On the summer evenings, little Hiawatha would hear

the pine-trees whisper to one another and the water lapping

in the lake, and he would see the fire-flies twinkle

in the twilight; and when he saw the moon and all the

dark spots on it he asked Nokomis what they were, and she

told him that a very angry warrior had once seized his grandmother[13]

and thrown her up into the sky at midnight, "right

up to the moon," said Nokomis, "and that is her body that

you see there."

When Hiawatha saw the rainbow, with the sun shining

on it, he said: "What is that, Nokomis?" and Nokomis

answered, saying: "That is the heaven of the flowers,

where all the flowers that fade on the earth blossom once

again." And when Hiawatha heard the owls hooting

through the night he asked Nokomis: "What are those?"

And Nokomis answered: "Those are the owls and the

owlets, talking to each other in their native language."

Then Hiawatha learned the language of all the birds

of the air, all about their nests, how they learned to fly

and where they went in winter; and he learned so much

that he could talk to them just as if he were a bird himself.

He learned the language of all the beasts of the forest, and

they told him all their secrets. The beavers showed him

how they built their houses, the squirrels took him to the

places where they hid their acorns, and the rabbits told him

why they were so timid. Hiawatha talked with all the

animals that he met, and he called them "Hiawatha's

brothers."

Nokomis had a friend called Iagoo the Boaster, because

he told so many stories about great deeds that he had never

done, and this Iagoo once made a bow for Hiawatha, and

said to him: "Take this bow, and go into the forest hunting.[14]

Kill a fine roebuck and bring us back his horns."

So Hiawatha went into the forest all alone with his bow

and arrows, and because he knew the language of the wild

things he could tell what all the birds and animals were

saying to him.

"Do not shoot us, Hiawatha!" said the robins; and the

squirrels scrambled in fright up the trunks of the trees,

coughing and chattering: "Do not shoot us, Hiawatha!"

But for once Hiawatha did not care or even hear what the

birds and beasts were saying to him.

At last he saw the tracks of the red deer, and he followed

them to the river bank, where he hid among the

bushes and waited until two antlers rose above the thicket

and a fine buck stepped out into the path and snuffed the

wind. Hiawatha's heart beat quickly and he rose to one

knee and aimed his arrow. "Twang!" went the bowstring,

and the buck leaped high into the air and fell down dead,

with the arrow in his heart. Hiawatha dragged the buck

that he had killed back to the wigwam of Nokomis, and

Nokomis and Iagoo were much pleased. From the buck-skin

they made a fine cloak for Hiawatha; they hung up

the antlers in the wigwam, and invited everybody in the

village to a feast of deer's flesh. And the Indians all came

and feasted, and called Hiawatha "Strong Heart."

[15]

IV

HIAWATHA AND MUDJEKEEWIS

THE years passed, and Hiawatha grew from a child

into a strong and active man. He was so wise that

the old men knew far less than he, and often asked him

for advice, and he was such a fine hunter that he never

missed his aim. He was so swift of foot that he could shoot

an arrow and catch it in its flight or let it fall behind him;

he was so strong that he could shoot ten arrows up into

the air, and the last of them would leave his bow before

the first had fallen to the ground. He had magic mittens

made of deer-skin, and when he wore them on his hands

he could break the rocks with them and grind the pieces

into powder; he had magic moccasins also—shoes made of

deer-skin that he tied about his feet, and when he put on

these he could take a mile at every step.

Hiawatha thought a great deal about his father, Mudjekeewis,

and often plagued Nokomis with questions about

him, until at last she told Hiawatha how his mother

had loved Mudjekeewis, who left her to die of sorrow; and

Hiawatha was so angry when he heard the story that his

heart felt like a coal of fire. He said to Nokomis: "I

will talk with Mudjekeewis, my father, and to find him I

will go to the Land of the Sunset, where he has his

kingdom."[16]

So Hiawatha dressed himself for travel and armed himself

with bow and a war-club, took his magic mittens and

his magic moccasins, and set out all alone to travel to the

kingdom of the West-wind. And although Nokomis

called after him and begged him to turn back, he would

not listen to her, but went away into the forest.

For days and days he traveled. He passed the Mississippi

River; he crossed the prairies where the buffaloes

were herding, and when he came to the Rocky Mountains,

where the panther and the grizzly bear have their homes,

he reached the Land of the Sunset, and the kingdom of

the West-wind. There he found his father, Mudjekeewis.

When Hiawatha saw his father he was as nearly afraid

as he had ever been in his life, for his father's cloudy hair

tossed and waved in the air and flashed like the star we

call the comet, trailing long streams of fire through the sky.

But when Mudjekeewis saw what a strong and handsome

man his son had grown to be, he was proud and happy;

for he knew that Hiawatha had all of his own early

strength and all the beauty of the dead Wenonah.

"Welcome, my son," said Mudjekeewis, "to the kingdom

of the West-wind. I have waited for you many years,

and have grown very lonely." And Mudjekeewis and

Hiawatha talked long together; but all the while Hiawatha

was thinking of his dead mother and the wrong that

had been done to her, and he became more and more angry.[17]

He hid his anger, however, and listened to what Mudjekeewis

told him, and Mudjekeewis boasted of his own

early bravery and of his body that was so tough that nobody

could do him any harm. "Can nothing hurt you?"

asked Hiawatha, and Mudjekeewis said: "Nothing but

the black rock yonder." Then he smiled at Hiawatha and

said: "Is there anything that can harm you, my son?"

And Hiawatha, who did not wish Mudjekeewis to know

that nothing in the world could do him injury, told him

that only the bulrush had such power.

Then they talked about other things—of Hiawatha's

brothers who ruled the winds, Wabun and Shawondasee

and Kabibonokka, and about the beautiful Wenonah, Hiawatha's

mother. And Hiawatha cried out then in fury:

"Father though you be, you killed Wenonah!" And he

struck with his magic mittens the black rock, broke it into

pieces, and threw them at Mudjekeewis; but Mudjekeewis

blew them back with his breath, and remembering what

Hiawatha had said about the bulrushes he tore them up

from the mud, roots and all, and used them as a whip to

lash his son.

Thus began the fearful fight between Hiawatha and his

father, Mudjekeewis. The eagle left his nest and circled

in the air above them as they fought; the bulrush bent and

waved like a tall tree in a storm, and great pieces of the

black rock crashed upon the earth. Three days the fight[18]

continued, and Mudjekeewis was driven back—back to

the end of the world, where the sun drops down into the

empty places every evening.

"Stop!" cried Mudjekeewis, "stop, Hiawatha! You

cannot kill me. I have put you to this trial to learn how

brave you are. Now I will give you a great prize. Go

back to your home and people, and kill all the monsters,

and all the giants and the serpents, as I killed the great

bear when I was young. And at last when Death draws

near you, and his awful eyes glare on you from the darkness,

I will give you a part of my kingdom and you shall

be ruler of the North-west wind."

Then the battle ended long ago among the mountains;

and if you do not believe this story, go there and see for

yourself that the bulrush grows by the ponds and rivers,

and that the pieces of the black rock are scattered all

through the valleys, where they fell after Hiawatha had

thrown them at his father.

Hiawatha started homeward, with all the anger taken

from his heart. Only once upon his way he stopped

and bought the heads of arrows from an old Arrow-maker

who lived in the land of the Indians called

Dacotahs. The old Arrow-maker had a daughter, whose

laugh was as musical as the voice of the waterfall

by which she lived, and Hiawatha named her by the

name of the rushing waterfall—"Minnehaha"—Laughing[19]

Water. When he reached his native village, all he told

to Nokomis was of the battle with his father. Of the

arrows and the lovely maiden, Minnehaha, he did not say

a word.

V

HIAWATHA'S FASTING

THE time came when Hiawatha felt that he must

show the tribes of Indians that he would do them

some great service, and he went alone into the forest

to fast and pray, and see if he could not learn how

to help his fellow-men and make them happy. In the

forest he built a wigwam, where nobody might disturb him,

and he went without food for seven nights and seven days.

The first day, he walked in the forest; and when he saw

the hare leap into the thicket and the deer dart away at

his approach he was very sad, because he knew that if the

animals of the forest should die, or go and hide where the

Indians could not hunt them, the Indians would starve

for want of food. "Must our lives depend on the hare

and on the red deer?" asked Hiawatha, and he prayed to

the Great Manito to tell him of some food that the Indians

might always be able to find when they were hungry.

The next day, Hiawatha walked by the bank of the

river, and saw the wild rice growing and the blueberries[20]

and the wild strawberries and the grape-vine that filled

the air with pleasant odors; and he knew that when cold

winter came, all this fruit would wither and the Indians

would have no more of it to eat. Again he prayed to the

Great Manito to tell him of some food that the Indians

might enjoy in winter and summer, in autumn and in

spring.

The third day that Hiawatha fasted, he was too weak

to walk about the forest, and he sat by the shore of the lake

and watched the yellow perch darting about in the sunny

water. Far out in the middle of the lake he saw Nahma,

the big sturgeon, leap into the air with a shower of spray

and fall back into the water with a crash; and every now

and then the pike would chase a school of minnows into

the shallow water at the edges of the lake and dart among

them like an arrow. And Hiawatha thought of how a

hot summer might dry up the lakes and rivers and kill the

fish, or drive them into such deep water that nobody could

catch them; and he called out to the Great Manito, asking

a third time for some food that the Indians could store

away and use when there was no game in the forest, and

no fruit on the river banks or in the fields, and no fish in

any of the lakes and rivers.

On the fourth day that Hiawatha fasted, he was so weak

from hunger that he could not even go out and sit beside[21]

the lake, but lay on his back in his wigwam and watched

the rising sun burn away the mist, and he looked up into

the blue sky, wondering if the Great Manito had heard his

prayers and would tell him of this food that he wished so

much to find. And just as the sun was sinking down

behind the hills, Hiawatha saw a young man with golden

hair coming through the forest toward his wigwam, and

the young man wore a wonderful dress of the brightest

green, with silky yellow fringes and gay tassels that waved

behind him in the wind.

The young man walked right into Hiawatha's wigwam

and said: "Hiawatha, my name is Mondamin, and I have

been sent by the Great Manito to tell you that he has

heard your prayers and will give you the food that you

wish to find. But you must work hard and suffer a great

deal before this food is given you, and you must now

come out of your wigwam and wrestle with me in the

forest."

Then Hiawatha rose from his bed of leaves and branches,

but he was so weak that it was all he could do to follow

Mondamin from the wigwam. He wrestled with Mondamin,

and as soon as he touched him his strength began to

return. They wrestled for a long time and at last Mondamin

said: "It is enough. You have wrestled bravely,

Hiawatha. To-morrow I will come again and wrestle[22]

with you." He vanished, and Hiawatha could not tell

whether he had sunk into the ground or disappeared into

the air.

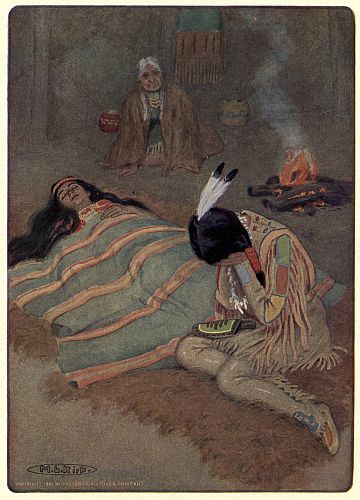

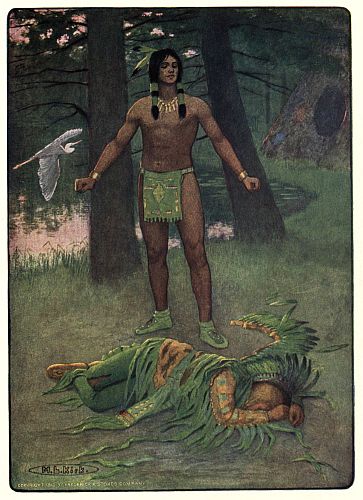

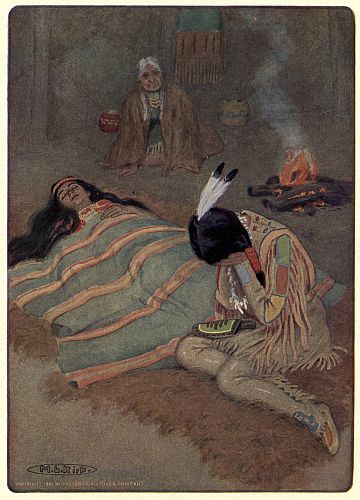

"DEAD HE LAY THERE IN THE SUNSET"—Page 153

"DEAD HE LAY THERE IN THE SUNSET"—Page 153

On the next day, when the sun was setting, Mondamin

came again to wrestle with Hiawatha, and the day after

that he came also and they wrestled even longer than

before. Then Mondamin smiled at Hiawatha and said

to him: "Three times, O Hiawatha, you have bravely

wrestled with me. To-morrow I shall wrestle with you

once again, and you will overcome me and throw me to the

earth and I shall seem to be dead. Then, when I am

lying still and limp on the ground, do you take off my gay

clothes and bury me where we have wrestled. And you

must make the ground above the place where I am buried

soft and light, and take good care that weeds do not grow

there and that ravens do not come there to disturb me,

until at last I rise again from the ground more beautiful

than ever."

True to his word, Mondamin came at sunset of the next

day, and he and Hiawatha wrestled together for the last

time. They wrestled after evening had come upon them,

until at last Hiawatha threw Mondamin to the ground,

who lay there as if dead.

Then Hiawatha took off all the gay green clothes that

Mondamin wore, and he buried Mondamin and made the

ground soft and light above the grave, just as he had been[23]

told to do. He kept the weeds from growing in the ground,

and kept the ravens from coming to the place, until at

last he saw a tiny little green leaf sticking up out of the

grave. The little leaf grew into a large plant, taller than

Hiawatha himself, and the plant had wonderful green

leaves and silky yellow fringes and gay tassels that waved

behind it in the wind. "It is Mondamin!" cried out Hiawatha,

and he called Nokomis and Iagoo to see the wonderful

plant that was to be the food that he had prayed

for to the Great Manito.

They waited until autumn had turned the leaves to

yellow, and made the tender kernels hard and shiny, and

then they stripped the husks and gathered the ears of the

wonderful Indian corn. All the Indians for miles around

had a great feast and were happy, because they knew that

with a little care they would have corn to eat in winter

and in summer, in autumn and in spring.

VI

HIAWATHA'S FRIENDS

HIAWATHA had two good friends, whom he had

chosen from all other Indians to be with him

always, and whom he loved more than any living

men. They were Chibiabos, the sweetest singer, and

Kwasind, the strongest man in the world; and they told

[24]

to Hiawatha all their secrets as he told his to them. Best

of all Hiawatha loved the brave and beautiful Chibiabos,

who was such a wonderful musician that when he sang

people flocked from villages far and near to listen to him,

and even the animals and birds left their dens and nests to

hear.

Chibiabos sang so sweetly that the brook would pause

in its course and murmur to him, asking him to teach its

waves to sing his songs and to flow as softly as his words

flowed when he was singing. The envious bluebird

begged Chibiabos to teach it songs as wild and wonderful

as his own; the robin tried to learn his notes of gladness,

and the lonely bird of night, the whippoorwill, longed to

sing as Chibiabos sang when he was sad. He could imitate

all the noises of the woodland, and make them sound even

sweeter than they really were, and by his singing he could

force the Indians to laugh or cry or dance, just as he chose.

The mighty Kwasind was also much beloved by Hiawatha,

who believed that next to wonderful songs and love

and wisdom great strength was the finest thing in the world

and the closest to perfect goodness; and never, in all the

years that men have lived upon the earth, has there been

another man so strong as Kwasind.

When he was a boy, Kwasind did not fish or play with

other children, but seemed very dull and dreamy, and his

father and mother thought that they were bringing up a[25]

fool. "Lazy Kwasind!" his mother said to him, "you never

help me with my work. In the summer you roam through

the fields and forests, doing nothing; and now that it is

winter you sit beside the fire like an old woman, and leave

me to break the ice for fishing and to draw the nets alone.

Go out and wring them now, where they are freezing with

the water that is in them; hang them up to dry in the sunshine,

and show that you are worth the food that you eat

and the clothes you wear on your back."

Without a word Kwasind rose from the ashes where he

was sitting, left the lodge and found the nets dripping and

freezing fast. He wrung them like a wisp of straw, but

his fingers were so strong that he broke them in a hundred

different places, and his strength was so great that he could

not help breaking the nets any more than if they were tender

cobwebs.

"Lazy Kwasind!" his father said to him, "you never help

me in my hunting, as other young men help their fathers.

You break every bow you touch, and you snap every arrow

that you draw. Yet you shall come with me and bring

home from the forest what I kill."

They went down to a deep and narrow valley by the

side of a little brook, where the tracks of bison and of deer

showed plainly in the mud; and at last they came to a place

where the trunks of heavy trees were piled like a stone wall

across the valley.[26]

"We must go back," said Kwasind's father; "we can

never scale those logs. They are packed so tightly that no

woodchuck could get through them, and not even a squirrel

could climb over the top," and the old man sat down to

smoke and rest and wonder what they were going to do;

but before he had finished his pipe the way lay clear, for

the strong Kwasind had lifted the logs as if they were

light lances, and had hurled them crashing into the depths

of the forest.

"Lazy Kwasind!" shouted the young men, as they ran

their races and played their games upon the meadows,

"why do you stay idle while we strive with one another?

Leave the rock that you are leaning on and join us. Come

and wrestle with us, and see who can pitch the quoit the

farthest."

Kwasind did not say a word in answer to them, but rose

and slowly turned to the huge rock on which he had been

leaning. He gripped it with both hands, tore it from the

ground and pitched it right into the swift Pauwating River,

where you can still see it in the summer months, as it towers

high above the current.

Once as Kwasind with his companions was sailing down

the foaming rapids of the Pauwating he saw a beaver in

the water—Ahmeek, the King of Beavers—who was

struggling against the savage current. Without a word,

Kwasind leaped into the water and chased the beaver in[27]

and out among the whirlpools. He followed the beaver

among the islands, dove after him to the bottom of the river

and stayed under water so long that his companions

believed him dead and cried out: "Alas, we shall see Kwasind

no more! He is drowned in the whirlpool!" But

Kwasind's head showed at last above the water and he

swam ashore, carrying the King of Beavers dead upon his

shoulders.

These were the sort of men that Hiawatha chose to be

his friends.

VII

HIAWATHA'S SAILING

ONCE Hiawatha was sitting alone beside the swift

and mighty river Taquamenaw, and he longed for

a canoe with which he might explore the river from

bank to bank, and learn to know all its rapids and its

shallows. And Hiawatha set about building himself a

canoe such as he needed, and he called upon the forest to

give him aid:

"Give me your bark, O Birch Tree!" cried Hiawatha;

"I will build me a light canoe for sailing that shall float

upon the river like a yellow leaf in autumn. Lay aside

your cloak, O Birch Tree, for the summer time is coming."

And the birch tree sighed and rustled in the breeze, murmuring

sadly: "Take my cloak, O Hiawatha!"[28]

With his knife Hiawatha cut around the trunk of the

birch-tree just beneath the branches until the sap came

oozing forth; and he also cut the bark around the tree-trunk

just above the roots. He slashed the bark from top

to bottom, raised it with wooden wedges and stripped it

from the trunk of the tree without a crack in all its golden

surface.

"Give me your boughs, O Cedar!" cried Hiawatha.

"Give me your strong and pliant branches, to make my

canoe firmer and tougher beneath me." Through all the

branches of the cedar there swept a noise as if somebody

were crying with horror, but the tree at last bent downward

and whispered: "Take my boughs, O Hiawatha."

He cut down the boughs of the cedar and made them into

a framework with the shape of two bows bent together, and

he covered this framework with the rich and yellow bark.

"Give me your roots, O Larch Tree!" cried Hiawatha,

"to bind the ends of my canoe together, that the water may

not enter and the river may not wet me!" The larch-tree

shivered in the air and touched Hiawatha's forehead with

its tassels, sighing: "Take them, take them!" as he tore the

fibres from the earth. With the tough roots he sewed the

ends of his canoe together and bound the bark tightly to

the framework, and his canoe became light and graceful in

shape. He took the balsam and pitch of the fir-tree and

smeared the seams so that no water might ooze in, and he[29]

asked for the quills of Kagh, the hedgehog, to make a necklace

and two stars for his canoe.

Thus did Hiawatha build his birch canoe, and all the

life and magic of the forest was held in it; for it had all the

lightness of the bark of the birch-tree, all the toughness of

the boughs of the cedar, and it danced and floated on the

river as lightly as a yellow leaf.

Hiawatha did not have any paddles for his canoe, and he

needed none, for he could guide it by merely wishing that

it should turn to the right or to the left. The canoe would

move in whatever direction he chose, and would glide over

the water swiftly or slowly just as he desired. All Hiawatha

had to do was to sit still and think where he cared to

have it take him. Never was there such a wonderful craft

before.

Then Hiawatha called to Kwasind, and asked for help

in clearing away all the sunken logs and all the rocks, and

sandbars in the river-bed, and he and Kwasind traveled

down the whole length of the river. Kwasind swam and

dove like a beaver, tugging at sunken logs, scooping out

the sandbars with his hands, kicking the boulders out of

the stream and digging away all the snags and tangles.

They went back and forth and up and down the river,

Kwasind working just as hard as he was able, and Hiawatha

showing him where he could find new logs and rocks,

and sandbars to remove, until together they made the channel[30]

safe and regular all the way from where the river rose

among the mountains in little springs to where it emptied

a wide and rolling sheet of water into the bay of Taquamenaw.

VIII

HIAWATHA'S FISHING

IN his wonderful canoe, Hiawatha sailed over the shining

Big-Sea-Water to go fishing and to catch with his

fishing-line made of cedar no other than the very King

of Fishes—Nahma, the big sturgeon. All alone Hiawatha

sailed over the lake, but on the bow of his canoe sat a

squirrel, frisking and chattering at the thought of all the

wonderful sport that he was going to see. Through the

calm, clear water Hiawatha saw the fishes swimming to

and fro. First he saw the yellow perch that shone like a

sunbeam; then he saw the crawfish moving along the sandy

bottom of the lake, and at last he saw a great blue shape

that swept the sand floor with its mighty tail and waved

its huge fins lazily backward and forward, and Hiawatha

knew that this monster was Nahma, the Sturgeon, King of

all the Fishes.

"Take my bait!" shouted Hiawatha, dropping his line of

cedar into the calm water. "Come up and take my bait, O

Nahma, King of Fishes!" But the great fish did not move,[31]

although Hiawatha shouted to him over and over again.

At last, however, Nahma began to grow tired of the endless

shouting, and he said to Maskenozha, the pike: "Take the

bait of this rude fellow, Hiawatha, and break his line."

Hiawatha felt the fishing-line tighten with a snap, and as

he pulled it in, Maskenozha, the pike, tugged so hard that

the canoe stood almost on end, with the squirrel perched on

the top; but when Hiawatha saw what fish it was that had

taken his bait he was full of scorn and shouted: "Shame

upon you! You are not the King of Fishes; you are only

the pike, Maskenozha!" and the pike let go of Hiawatha's

line and sank back to the bottom, very much ashamed.

Then Nahma said to the sunfish, Ugudwash: "Take

Hiawatha's bait, and break his line! I am tired of his

shouting and his boasting," and the sunfish rose up through

the water like a great white moon. It seized Hiawatha's

line and struggled so that the canoe made a whirlpool in

the water and rocked until the waves it made splashed

upon the beaches at the rim of the lake; but when Hiawatha

saw the fish he was very angry and shouted out again:

"Oh shame upon you! You are the sunfish, Ugudwash,

and you come when I call for Nahma, King of Fishes!" and

the sunfish let go of Hiawatha's line and sank to the bottom,

where he hid among the lily stems.

Then Nahma, the great sturgeon, heard Hiawatha shouting

at him once again, and furious he rose with a swirl to the[32]

top of the water; leaped in the air, scattering the spray on

every side, and opening his huge jaws he made a rush at the

canoe and swallowed Hiawatha, canoe and all.

Into the dark cave of Nahma's giant maw, Hiawatha in

his canoe plunged headlong, as a log rushes down a roaring

river in the springtime. At first he was frightened, for it

was so inky black that he could not see his hand before his

face; but at last he felt a great heart beating in the darkness,

and he clenched his fist and struck the giant heart with all

his strength. As he struck it, he felt Nahma tremble all

over, and he heard the water gurgle as the great fish rushed

through it trying to breathe, and Hiawatha struck the

mighty heart yet another heavy blow.

Then he dragged his canoe crosswise, so that he might not

be thrown from the belly of the great fish and be drowned

in the swirling water where Nahma was fighting for life,

and the little squirrel helped Hiawatha drag his canoe into

safety and tugged and pulled bravely at Hiawatha's side.

Hiawatha was grateful to the little squirrel, and told him

that for a reward the boys should always call him Adjidaumo,

which means "tail-in-the-air," and the little squirrel

was much pleased.

At last everything became quiet, and Nahma, the great

sturgeon, lay dead and drifted on the surface of the water

to the shore, where Hiawatha heard him grate upon the

pebbles. There was a great screaming and flapping of[33]

wings outside, and finally a gleam of light shone to the

place where Hiawatha was sitting, and he could see the

glittering eyes of the sea-gulls, who had crawled into the

open mouth of Nahma and were peering down his gullet.

Hiawatha called out to them: "O my Brothers, the Sea-Gulls,

I have killed the great King of Fishes, Nahma, the

sturgeon. Scratch and tear with your beaks and claws

until the opening becomes wider and you can set me free

from this dark prison! Do this, and men shall always call

you Kayoshk, the sea-gulls, the Noble Scratchers."

The sea-gulls set to work with a will, and scratched and

tore at Nahma's ribs until there was an opening wide

enough for Hiawatha and the squirrel to step through and

to drag the canoe out after them. Hiawatha called

Nokomis, pointed to the body of the sturgeon and said:

"See, Nokomis, I have killed Nahma, the King of Fishes,

and the sea-gulls feed upon him. You must not drive

them away, for they saved me from great danger; but when

they fly back to their nests at sunset, do you bring your pots

and kettles and make from Nahma's flesh enough oil to last

us through the winter."

Nokomis waited until sunset, when the sea-gulls had

flown back to their homes in the marshes, and she set

to work with all her pots and kettles to make yellow oil

from the flesh of Nahma. She worked all night long until

the sun rose again and the sea-gulls came back screeching[34]

and screaming for their breakfast; and for three days and

three nights the sea-gulls and Nokomis took turns in stripping

the greasy flesh of Nahma from his ribs, until nothing

was left. Then the sea-gulls flew away for good and all,

Nokomis poured her oil into great jars, and on the sand was

only the bare skeleton of Nahma, who had once been the

biggest and the strongest fish that ever swam.

IX

HIAWATHA AND THE PEARL-FEATHER

ONCE Nokomis was standing with Hiawatha beside

her upon the shore of the Big-Sea-Water, watching

the sunset, and she pointed to the west, and said to

Hiawatha: "There is the dwelling of the Pearl-Feather, the

great wizard who is guarded by the fiery snakes that coil

and play together in the black pitch-water. You can see

them now." And Hiawatha beheld the fiery snakes twist

and wriggle in the black water and coil and uncoil themselves

in play. Nokomis went on: "The great wizard

killed my father, who had come down from the moon to find

me. He killed him by wicked spells and by sly cunning,

and now he sends the rank mist of marshes and the deadly

fog that brings sickness and death among our people.

Take your bow, Hiawatha," said Nokomis, "and your war-club

and your magic mittens. Take the oil of the sturgeon,

[35]

Nahma, so that your canoe may glide easily through the

sticky black pitch-water, and go and kill this great wizard.

Save our people from the fever that he breathes at them

across the marshes, and punish him for my father's death."

Swiftly Hiawatha took his war-club and his arrows and

his magic mittens, launched his birch canoe upon the water

and cried: "O Birch Canoe, leap forward where you see the

snakes that play in the black pitch-water. Leap forward

swiftly, O my Birch Canoe, while I sing my war-song," and

the canoe darted forward like a live thing until it reached

the spot where the fiery serpents were sporting in the water.

"Out of my way, O serpents!" cried Hiawatha, "out of

my way and let me go to fight with Pearl-Feather, the

awful wizard!" But the serpents only hissed and answered:

"Go back, Coward; go back to old Nokomis,

Faint-heart!"

Then Hiawatha took his bow and sent his arrows singing

among the serpents, and at every shot one of them was

killed, until they all lay dead upon the water.

"Onward, my Birch Canoe!" cried Hiawatha; "onward

to the home of the great wizard!" and the canoe darted forward

once again.

It was a strange, strange place that Hiawatha had

entered with his birch canoe! The water was as black as

ink, and on the shores of the lake dead men lit fires that

twinkled in the darkness like the eyes of a wicked old[36]

witch. Awful shrieks and whistling echoed over the

water, and the heron flapped about the marshes to tell all

the evil beings who lived there that Hiawatha was coming

to fight with the great wizard.

Hiawatha sailed over this dismal lake all night long, and

at last, when the sun rose, he saw on the shore in front of him

the wigwam of the great magician, Pearl-Feather. The

canoe darted ahead faster and faster until it grated on the

beach, and Hiawatha fitted an arrow to his bowstring and

sent it hissing into the open doorway of the wigwam.

"Come out and fight me, Pearl-Feather!" cried Hiawatha;

"come out and fight me if you dare!"

Then Pearl-Feather stepped out of his wigwam and

stood in the open before Hiawatha. He was painted red

and yellow and blue and was terrible to see. In his hand

was a heavy war-club, and he wore a shirt of shining wampum

that would keep out an arrow and break the force of

any blow.

"Well do I know you, Hiawatha!" shouted Pearl-Feather

in a deep and awful voice. "Go back to Nokomis,

coward that you are; for if you stay here, I will kill you as

I killed her father."

"Words are not as sharp as arrows," answered Hiawatha,

bending his bow.

Then began a battle even more terrible than the one

among the mountains when Hiawatha fought with Mudjekeewis,[37]

and it lasted all one summer's day. For Hiawatha's

arrows could not pierce Pearl-Feather's shirt of

wampum, and he could not break it with the blows of his

magic mittens.

At sunset Hiawatha was so weary that he leaned on his

bow to rest. His heavy war-club was broken, his magic

mittens were torn to pieces, and he had only three arrows

left. "Alas," sighed Hiawatha, "the great magician is

too strong for me!"

Suddenly, from the branches of the tree nearest him, he

heard the woodpecker calling to him: "Hiawatha, Hiawatha,"

said the woodpecker, "aim your arrows at the tuft

of hair on Pearl-Feather's head. Aim them at the roots of

his long black hair, for there alone can you do him any

harm." Just then Pearl-Feather stooped to pick up a big

stone to throw at Hiawatha, who bent his bow and struck

Pearl-Feather with an arrow right on the top of the head.

Pearl-Feather staggered forward like a wounded buffalo.

"Twang!" went the bowstring again, and the wizard's

knees trembled beneath him, for the second arrow had

struck in the same spot as the first and had made the wound

much deeper. A third arrow followed swiftly, and Pearl-Feather

saw the eyes of Death glare at him from the

darkness, and he fell forward on his face right at the feet

of Hiawatha and lay there dead.

Then Hiawatha called the woodpecker to him, and as[38]

a mark of gratitude he stained the tuft of feathers on the

woodpecker's head with the blood of the dead Pearl-Feather,

and the woodpecker wears his tuft of blood-red

feathers to this day.

Hiawatha took the shirt of wampum from the dead

wizard as a sign of victory, and from Pearl-Feather's wigwam

he carried all the skins and furs and arrows that he

could find, and they were many. He loaded his canoe

with them and sped homeward over the pitch-water, past

the dead bodies of the fiery serpents until he saw Chibiabos

and Kwasind and Nokomis waiting for him on the shore.

All the Indians assembled and gave a feast in Hiawatha's

honor, and they sang and danced for joy because

the great wizard would never again send sickness and

death among them. And Hiawatha took the red crest of

the woodpecker to decorate his pipe, for he knew that to

the woodpecker his victory was due.

X

HIAWATHA'S WOOING

"WOMAN is to man as the cord is to the bow,"

thought Hiawatha. "She bends him, yet

obeys him; she draws him, yet she follows. Each is useless

without the other." Hiawatha was dreaming of the

lovely maiden, Minnehaha, whom he had seen in the country

of the Dacotahs.

[39]"Do not wed a stranger, Hiawatha," warned the old

Nokomis; "do not search in the east or in the west to win

a bride. Take a maid of your own people, for the homely

daughter of a neighbor is like the pleasant fire on the

hearth-stone, while the stranger is cold and distant, like

the starlight or the light of the pale moon."

But Hiawatha only smiled and answered: "Dear Nokomis,

the fire on the hearth-stone is indeed pleasant and

warm, but I love the starlight and the moonlight better."

"Do not bring home an idle woman," said old Nokomis,

"bring not home a maiden who is unskilled with the needle

and will neither cook nor sew!" And Hiawatha answered:

"Good Nokomis, in the land of the Dacotahs lives

the daughter of an Arrow-maker, and she is the most beautiful

of all the women in the world. Her name is Minnehaha,

and I will bring her home to do your bidding and to

be your firelight, your moonlight, and your starlight, all in

one."

"Ah, Hiawatha," warned Nokomis, "bring not home a

maid of the Dacotahs! The Dacotahs are fierce and cruel

and there is often war between our tribe and theirs."

Hiawatha laughed and answered: "I will wed a maid of

the Dacotahs, and old wars shall be forgotten in a new and

lasting peace that shall make the two tribes friends forevermore.

For this alone would I wed the lovely Laughing

Water if there were no other reason."[40]

Hiawatha left his wigwam for the home of the old

Arrow-maker, and he ran through the forest as lightly as

the wind, until he heard the clear voice of the Falls of

Minnehaha.

At the sunny edges of the forest a herd of deer were

feeding, and they did not see the swift-footed runner until

he sent a hissing arrow among them that killed a roebuck.

Without pausing, Hiawatha caught up the deer and

swung it to his shoulder, running forward until he came

to the home of the aged Arrow-maker.

The old man was sitting in the doorway of his wigwam,

and at his side were all his tools and all the arrows he was

making. At his side, also, was the lovely Minnehaha,

weaving mats of reeds and water-rushes, and the old man

and the young maiden sat together in the pleasant contrast

of age and youth, the one thinking of the past, the

other dreaming of the future.

The old man was thinking of the days when with such

arrows as he now was making he had killed deer and

bison, and had shot the wild goose on the wing. He remembered

the great war-parties that came to buy his

arrows, and how they could not fight unless he had arrow-*heads

to sell. Alas, such days were over, he thought

sadly, and no such splendid warriors were left on earth.

The maiden was dreaming of a tall, handsome hunter,

who had come one morning when the year was young to[41]

purchase arrows of her father. He had rested in their

wigwam, lingered and looked back as he was leaving, and

her father had praised his courage and his wisdom. Would

the hunter ever come again in search of arrows, thought

the lovely Minnehaha, and the rushes she was weaving lay

unfingered in her lap.

Just then they heard a rustle and swift footsteps in the

thicket, and Hiawatha with the deer upon his shoulders

and a glow upon his cheek and forehead stood before them

in the sunlight.

"Welcome, Hiawatha," said the old Arrow-maker in a

grave but friendly tone, and Minnehaha's light voice

echoed the deep one of her father, saying: "Welcome,

Hiawatha."

Together the old Arrow-maker and Hiawatha entered

the wigwam, and Minnehaha laid aside her mat of rushes

and brought them food and drink in vessels of earth and

bowls of basswood. Yet she did not say a word while she

was serving them, but listened as if in a dream to what

Hiawatha told her father about Nokomis and Chibiabos

and the strong man, Kwasind, and the happiness and peace

of his own people, the Ojibways. Hiawatha finished

his words by saying very slowly: "That this peace may

always be among us and our tribes become as brothers to

each other, give me the hand of your daughter, Minnehaha,

the loveliest of women."[42]

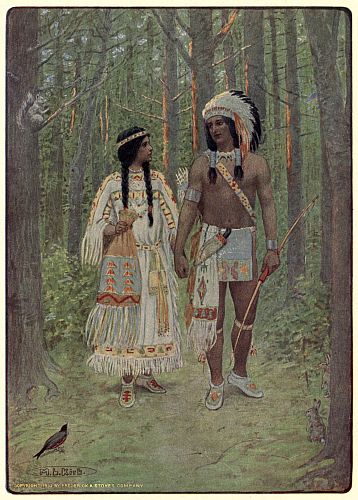

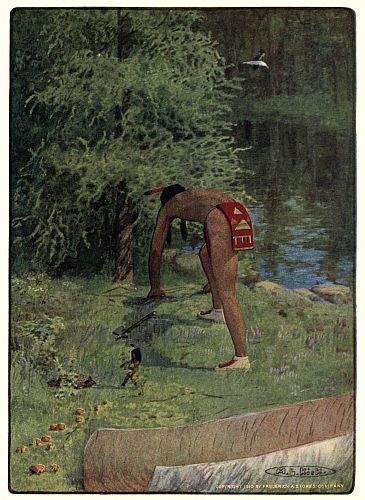

"PLEASANT WAS THE JOURNEY HOMEWARD"—Page 199

"PLEASANT WAS THE JOURNEY HOMEWARD"—Page 199

The aged Arrow-maker paused before he answered,

looked proudly at Hiawatha and lovingly at his daughter,

and then said:

"You may have her if she wishes it. Speak, Minnehaha,

and let us know your will."

The lovely Minnehaha seemed more beautiful than ever

as she looked first at Hiawatha and then at her old father.

Softly she took the seat beside Hiawatha, blushing as she

answered: "I will follow you, my husband."

Thus did Hiawatha win the daughter of the ancient

Arrow-maker. Together he and his bride left the wigwam

hand in hand and went away over the meadows,

while the old Arrow-maker with shaded eyes gazed after

them and called out sadly: "Good-bye, Minnehaha! Good-bye

my lovely daughter!"

They walked together through the sunlit forest, and all

the birds and animals gazed at them from among the leaves

and branches.

When they came to swift rivers, Hiawatha lifted Minnehaha

and carried her across, and in his strong arms she

seemed lighter than a willow-leaf or the plume upon

his headgear. At night he cleared away the thicket and

built a lodge of branches; he made a bed of hemlock boughs

and kindled a fire of pine-cones before the doorway, and

Adjidaumo, the squirrel, climbed down from his nest and[43]

kept watch, while the two lovers slept in their lodge beneath

the stars.

XI

HIAWATHA'S WEDDING FEAST

A GREAT feast was prepared by Hiawatha to

celebrate his wedding. That the feast might be

one of joy and gladness, the sweet singer Chibiabos

sang his love-songs; that it might be merry, the handsome

Pau-Puk-Keewis danced his liveliest dances; and to

make the wedding guests even more content, Iagoo, the

great boaster, told them a wonderful story. Oh, but it

was a splendid feast that Nokomis prepared at the bidding

of Hiawatha! She sent messengers with willow-wands

through all the village as a sign that all Ojibways

were invited, and the wedding guests wore their very

brightest garments—rich fur robes and wampum-belts,

beads of many colors, paint and feathers and gay tassels.

All the bowls at the feast were made of white and shining

basswood; all the spoons were made of bison horn, as black

as ink and polished until the black was as bright as silver,

and the Indians feasted on the flesh of the sturgeon and

the pike, on buffalo marrow and the hump of the bison

and the haunch of the red deer. They ate pounded

[44]

meat called pemican and the wild rice that grew by the

river-bank and golden-yellow cakes of Indian corn. It was

a feast indeed!

But the kind host Hiawatha did not take a mouthful of

all this tempting food. Neither did Minnehaha nor Nokomis,

but all three waited on their guests and served them

carefully until their wants were generously satisfied.

When all had finished, old Nokomis filled from an ample

otter pouch the red stone pipes with fragrant tobacco of

the south, and when the blue smoke was rising freely she

said: "O Pau-Puk-Keewis, dance your merry Beggar's

Dance to please us, so the time may pass more pleasantly

and our guests may be more gay."

Pau-Puk-Keewis rose and stood amid the guests. He

wore a white shirt of doeskin, fringed with ermine and

covered with beads of wampum. He wore deerskin

leggings, also fringed with ermine and with quills

of Kagh, the hedgehog. On his feet were buck-skin

moccasins, richly embroidered, and red foxes' tails

to flourish while he danced were fastened to the heels. A

snowy plume of swan's down floated over his head, and he

carried a gay fan in one hand and a pipe with tassels in the

other.

All the warriors disliked Pau-Puk-Keewis, and called

him coward and idler; but he cared not at all, because

he was so handsome that all the women and the maidens[45]

loved him. To the sound of drums and flutes and singing

voices Pau-Puk-Keewis now began the Dance of

Beggars.

First he danced with slow steps and stately motion in

and out of the shadows and the sunshine, gliding like a

panther among the pine-trees; but his steps became faster

and faster and wilder and wilder, until the wind and dust

swept around him as he danced. Time after time he

leaped over the heads of the assembled guests and rushed

around the wigwam, and at last he sped along the shore

of the Big-Sea-Water, stamping on the sand and tossing it

furiously in the air, until the wind had become a whirlwind

and the sand was blown in great drifts like snowdrifts

all over the shore.

There they have stayed until this day, the great Sand

Hills of the Nagow Wudjoo.

When the Beggar's Dance was over, Pau-Puk-Keewis

returned and sat down laughing among the guests and

fanned himself as calmly as if he had not stirred from his

seat, while all the guests cried out: "Sing to us, Chibiabos,

sing your love songs!" and Hiawatha and Nokomis said:

"Yes, sing, Chibiabos, that our guests may enjoy themselves

all the more, and our feast may pass more gayly!"

Chibiabos rose, and his wonderful voice swelled all the

echoes of the forest, until the streams paused in their

courses, and the listening beavers came to the surface of[46]

the water so that they might hear. He sang so sweetly

that his voice caused the pine-trees to quiver as if a wind

were passing through them, and strange sounds seemed to

run along the earth. All the Indians were spellbound by

his singing, and sat as if they had been turned to stone.

Even the smoke ceased to rise from their pipes while

Chibiabos sang, but when he had ended they shouted with

joy and praised him in loud voices.

Iagoo, the mighty boaster, alone did not join in the roar

of praise, for he was jealous of Chibiabos, and longed to

tell one of his great stories to the Indians. When Iagoo

heard of any adventure he always told of a greater one that

had happened to himself, and to listen to him, you would

think that nobody was such a mighty hunter and nobody

was such a valiant fighter as he. If you would only believe

him, you would learn nobody had ever shot an arrow

half so far as he had, that nobody could run so fast, or

dive so deep, or leap so high, and that nobody in the wide

world had ever seen so many wonders as the brave, great,

and wonderful Iagoo.

This was the reason that his name had become a byword

among the Indians; and whenever a hunter spoke too

highly of his own deeds, or a warrior talked too much of

what he had done in battle, his hearers shouted: "See,

Iagoo is among us!"

But it was Iagoo who had carved the cradle of Hiawatha[47]

long ago, and who had taught him how to make his

bow and arrows. And as he sat at the feast, old and ugly

but very eager to tell of his adventures, Nokomis said to

him: "Good Iagoo, tell us some wonderful story, so that

our feast may be more merry," and Iagoo answered like a

flash: "You shall hear the most wonderful story that has

ever been heard since men have lived upon the earth. You

shall hear the strange and marvelous tale of Osseo and his

father, King of the Evening Star."

XII

THE SON OF THE EVENING STAR

"SEE the Star of Evening!" cried Iagoo; "see how

it shines like a bead of wampum on the robes of

the Great Spirit! Gaze on it, and listen to the story of

Osseo!

"Long ago, in the days when the heavens were nearer

to the earth than they are now, and when the spirits and

gods were better known to all men, there lived a hunter in

the Northland who had ten daughters, young and beautiful,

and as tall as willow-wands. Oweenee, the youngest

of these, was proud and wayward, but even fairer than

her sisters. When the brave and wealthy warriors came as

suitors, each of the ten sisters had many offers, and all

except Oweenee were quickly married; but Oweenee[48]

laughed at her handsome lovers and sent them all away.

Then she married poor, ugly old Osseo, who was bowed

down with age, weak with coughing, and twisted and

wrinkled like the roots of an oak-tree. For she saw that

the spirit of Osseo was far more beautiful than were the

painted figures of her handsome lovers.

"All the suitors whom she had refused to marry, and they

were many, came and pointed at her with jeers and laughter,

and made fun of her and of her husband; but she said

to them: 'I care not for your feathers and your wampum;

I am happy with Osseo.'

"It happened that the sisters were all invited to a great

feast, and they were walking together through the forest,

followed by old Osseo and the fair Oweenee; but while

all the others chatted gayly, these two walked in silence.

Osseo often stopped to gaze at the Star of Evening, and at

last the others heard him murmur: 'Oh, pity me, pity me,

my Father!' 'He is praying to his father,' said the eldest

sister. 'What a shame that the old man does not stumble in

the path and break his neck!' and the others all laughed

so heartily at the wicked joke that the forest rang with

merriment.

"On their way through the thicket, lay a hollow oak that

had been uprooted by a storm, and when Osseo saw it he

gave a cry of anguish, and leaped into the mighty tree.

He went in an old man, ugly and bent and hideous with[49]

wrinkles. He came out a splendid youth, straight as an

arrow, handsome and very strong. But Osseo was not

happy in the change that had come over him. Indeed, he

was more sorrowful than ever before, because at the same

instant that he recovered his lost youth, Oweenee was

changed into a tottering old woman, wasted and worn and

ugly as a witch. And her nine hard-hearted sisters and

their husbands laughed long and loud, until the forest

echoed once again with their wicked merriment.

"Osseo, however, did not turn from Oweenee in her

trouble, but took her brown and withered hand, called her

sweetheart and soothed her with kind words, until they

came to the lodge in the forest where the feast was being

given. They sat down to the feast, and all were joyous

except Osseo, who would taste neither food nor drink, but

sat as if in a dream, looking first at the changed Oweenee,

then upward at the sky. All at once he heard a voice come

out of the empty air and say to him: 'Osseo, my son, the

spells that bound you are now broken, and the evil charms

that made you old and withered before your time have all

been wished away. Taste the food before you, for it is

blessed and will change you to a spirit. Your bowls and

your kettles shall be changed to silver and to wampum,

and shine like scarlet shells and gleam like the firelight;

and all the men and women but Oweenee shall be changed

to birds.'[50]

"The voice Osseo heard was taken by the others for the

voice of the whippoorwill, singing far off in the lonely

forest, and they did not hear a word of what was said.

But a sudden tremor ran through the lodge where they sat

feasting, and they felt it rise in the air high up above the

tree-tops into the starlight. The wooden dishes were

changed into scarlet shells, the earthen kettles were changed

into silver bowls, and the bark of the roof glittered like the

backs of gorgeous beetles.

"Then Osseo saw that the nine beautiful sisters of Oweenee

and their husbands, were changed into all sorts

of different birds. There were jays and thrushes and magpies

and blackbirds, and they flew about the lodge and sang

and twittered in many different keys. Only Oweenee was

not changed, but remained as wrinkled and old and ugly

as before; and Osseo, in his disappointment, gave a cry of

anguish such as he had uttered by the oak tree when lo

and behold! all Oweenee's former youth and loveliness

returned to her. The old woman's staff on which she had

been leaning became a glittering silver feather, and her

tattered dress was changed into a snowy robe of softest

ermine.

"The wigwam trembled once again and floated through

the sky until at last it alighted on the Evening Star as

gently as thistledown drops to the water, and the ruler of[51]

the Evening Star, the father of Osseo, came forward to

greet his son.

"'My son,' he said, 'hang the cage of birds that you

bring with you at the doorway of my wigwam, and then do

you and Oweenee enter,' and Osseo and Oweenee did as

they were told, entered the wigwam and listened to the

words of Osseo's father.

"'I have had pity on you, my Osseo,' he began. 'I have

given back to you your youth and beauty; and I have

changed into birds the sisters of Oweenee and their husbands,

because they laughed at you and could not see that

your spirit was beautiful. When you were an ugly old

man, only Oweenee knew your heart. But you must take

heed, for in the little star that you see yonder lives an evil

spirit, the Wabeno; and it is he who has brought all this

sorrow upon you. Take care that you never stand in the

light of that evil star. Its gleams are used by the Wabeno

as his arrows, and he sits there hating all the world and

darting forth his poisonous beams of baleful light to injure

all who stray within his reach.'

"For many years Osseo and his father and Oweenee